“All we are doing is looking at the time line; from the moment the customer gives us an order to the point when we collect cash. We are reducing that time line by removing the non-value-added wastes.” -Taiichi Ohno, Father of the Toyota Production System

As Taiichi Ohno explains in this statement above, Lean is about removing waste from processes. This is one of the fundamental principles of Lean. Being lean means systematically removing anything impeding the free flow of value to the receiving party. But what exactly is “waste”?

Waste can mean many different things to different people, but in Lean it has a very specific definition. In fact waste can be broken down to 7 simple elements called the “7 wastes”.

The 7 wastes are:

- Transportation

- Inventory

- Motion

- Waiting

- Overproduction

- Over processing

- Defects

Transportation- moving products and materials from one location to another. When you are transporting goods you are adding costs without adding value. Not only that, you are also creating opportunities to damage or lose products during transport. This is why transportation, although often necessary, is considered “waste”. Whenever you can find a way to eliminate or reduce transportation from the process, you will increase speed while reducing costs. Examples include moving products long distances from one location to another, carrying products from one area to another, transporting files, etc.

Inventory- any material, product, or service that is waiting to be processed or used. Inventory is all around us almost everywhere we go – grocery stores, restaurants, warehouses, shopping malls. In many cases inventory is good and it allows customers to get products faster, but there are many inherent risks and problems that come with storing inventory. Inventory is the result of one of the other seven wastes – Overproduction. When you have inventory, you have to spend money to transport it, store, count it, and even find it when it gets lost. The longer inventory sits, the greater the risks it can get lost or damaged. This is why inventory, while useful when needed, is considered to be one of the seven wastes. A better alternative is to deliver customers what they need in the moment they need it – without the need to store inventory. If you can achieve that, your costs and risks will be significantly less in most cases. When you see inventory in your process, it’s a potential opportunity to create a better customer experience and more efficient workflow. Examples include extra food on shelves, warehouses filled with products, car lots full of cars, a stack of boxes in the corner waiting to be used later, etc.

Motion- any movement including typing, clicking, twisting, turning, bending, reaching, and walking. Any lazy person will tell you that motion is wasted energy to be avoided at all costs. All joking aside, the more motion required to deliver a product or service the greater the costs and the slower the speed. Motion also requires energy exertion by operators and can add to fatigue and even risk of injury. This is especially true for repeatable processes that happen over and over again. The tiniest motion can add up quickly when it’s being repeated over and over again. Some companies have saved millions of dollars on production lines simply by moving build materials a few inches closer to the operators. It’s easy to see why motion is considered one of the seven wastes, and anytime you can reduce or eliminate it all together you will reduce your costs and improve your speed of delivery to customers. Examples include reaching to grab something, bending over to lift something up, typing or filling out fields on a computer, walking across the room to grab something, etc.

Waiting- a period of pause or delay. Tom Petty had it right: the waiting is the hardest part. Whether it’s an endless, unmoving queue, being stuck in idle while you wait for an approval to proceed, or simply a slow connection speed, we’ve all experienced waiting and the accompanying sense of helplessness and lost productivity. This is why waiting is one of the worst of the seven wastes. It causes frustration with employees as well as customers. When you see waiting occurring in your process, it’s an opportunity to improve the customer experience and create faster delivery. Shorter wait times than your competitors can be a real differentiator for many businesses. Examples of waiting include ER waiting rooms, waiting in line, waiting for a package to be delivered, waiting for an approval, waiting for an email, etc.

Overproduction- producing more than is needed by the customer. Overproduction is considered the mother of all wastes because it causes all the other wastes to occur. When you produce more of something than you need, then you have inventory you have to store. You have to move the inventory which causes both motion and transportation. This increases the risk of defects and over processing. All of these things add complexity and costs to your business. Even though there are so many negatives associated with overproduction it can often be difficult to avoid or to eliminate. Due to long production processes, many companies have to build products before they are needed by customers. This means they have to estimate or guess how much to build and will often build extra just in case. This allows customers to obtain products instantly when they want them even though the production process is lengthy. So as you can see, overproduction is often used to improve delivery despite the costs that come with it. In the event that you can shorten your production process and get customers what they want, when they need it, you can reduce or eliminate overproduction without sacrificing customer deliverability. Be careful when working to eliminate overproduction your process is ready to deliver faster and you won’t be harming customer deliverability. Examples of overproduction include pre-making hamburgers before orders come in, shipping too many cell phones to stores that never get sold, making a bunch of red cars when more customer want blue, sending emails to people who don’t need them (reply all), etc.

Over processing- doing more than is necessary. When there are too many non-value-added steps to achieve a given outcome, you’ve got over processing. Examples include too many operations to complete a phase of work, the effort needed to inspect and fix defects arising from poor tool or product design, and redundant data entry due to a lack of integration between multiple systems. When overproduction occurs, you make too many of something. By contrast, with over processing you made just the right amount but you did too many extra non-value add steps as you did it. Another way to think about it is building a customer an expensive Ferrari when all they wanted was a simple Corolla – doing way more than the customer wants or needs. Examples in the office include re-doing something because it was done incorrectly the first time, printing a document so you can scan it back into the computer as a pdf, etc.

Defects- products or services that are broken or do not meet the needs of the customer. Everyone has experienced a defect of some kind: errors, inaccurate or incomplete information or flawed products. It’s obviously important to reduce the probability of these things happening. Surprisingly, however, it’s not always a top priority. According to a 2010 survey from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, one in every seven Medicare patients in hospitals is subjected to a serious medical mistake, contributing to the deaths of an estimated 180,000 people a year. Of those, roughly 80,000 were caused by errors that could have been caught and prevented, with the simplest of methods — standardized checklists like those used by every airplane pilot — as surgeon/author Atul Gawande points out in his book The Checklist Manifesto. Examples in the office include typos, incorrect information, incorrect reports, boring training classes, etc.

There is an acronym to help you remember what the 7 wastes are. It is TIMWOOD:

- Transportation

- Inventory

- Motion

- Waiting

- Overproduction

- Over processing

- Defects

When applying lean, you start with examining the process from the customer’s perspective. This first question is always “What does the customer want from this process?” (Both the internal customer at the next steps in the production line and the final, external customer.) This defines value. Through a customer’s eyes, you can observe a process and separate the value-added steps from the non-value-added steps.

Ohno Circle- Watch and Think for Yourself

Taiichi Ohno spent a great deal of time on the shop floor at Toyota, learning to map the activities that added value to the product and getting rid of non-value-adding wastes. There are many stories about the famous Ohno circle. In his book “The Toyota Way”, Jeffrey Liker recounts an interview where he was able to speak in person with Teruyuki Minoura, who at the time was president of Toyota Motor Manufacturing, North America. He learned lean directly from the master and part of his early education at Toyota was standing in a circle:

Minoura: Mr. Ohno wanted us to draw a circle on the floor of a plant and then we were told, ‘Stand in that and watch the process and think for yourself,’ and then he didn’t even give you any hint of what to watch for. This is the real essence of lean.

Liker: How long did you stand in the circle?

Minoura: Eight hours!

Liker: Eight hours?!

Minoura: In the morning Mr. Ohno came to request that I stay in the circle until supper and after that Mr. Ohno came to check and ask me what I was seeing. And of course, I answered, “There were so many problems in the process….” But Mr. Ohno didn’t hear. He was just looking.

Liker: And what happened at the end of the day?

Minoura: It was near dinner time. He came to see me. He didn’t take any time to give any feedback. He just said gently, “Go home”.

Of course it is difficult to imagine this training happening in a U.S. factory. Most young engineers would be irritated if you told them to draw a circle and stand for 30 minutes, let alone all day. But Minoura understood this was an important lesson as well as an honor to be taught in this way by the master of lean. What exactly was Ohno teaching? The power of deep observation. He was teaching Minoura to think for himself about what he was seeing, that is, to question, analyze, and evaluate.

Perfection is extremely rare, which means there is waste in every process. Leaders should watch a process to find wastes that if removed will provide a process that is easier to execute and deliver a more perfect service or product. It’s a simple activity that doesn’t require a graduate degree or numberless years of experience. Simply block out time, watch and create an action plan for improvement. Teams can take a time out together from the daily grind to select a process to watch. Those who do the activity or task should be given time to experiment with their ideas for making the process better. This can engage each of the team members and provide a way for the team to work together providing better services or products to their customers.

1-It’s Time to Wage an All-Out War on Waste, Matthew E. May

Individual Kaizen

“Kaizen” is a compound Japanese word. “Kai” is translated to change, while “Zen” means to make good or make better. Kaizen grows out of the famous Toyota Production System where the focus is on engaging employees in ongoing, small, continuous improvements.

When you look for, and eliminate, the seven wastes from your process you are changing the process to make it better. This is called an individual kaizen. In fact, the easiest and best way to practice kaizen is to do it yourself. These will typically be small incremental improvements that are quick and easy to implement. These type of improvements usually don’t have huge results or make a big improvement to our business. Over time, however, as more and more individual kaizens are completed the cumulative results can be enormous. There is a lot of power in this principle, and this is the best, easiest, and fastest way for a company to do continuous improvements and always stay ahead of competitors.

How the CIU continuous improvement system comes together

As you hopefully recall from what you have learned about lean, achieving good quality is built on a foundation of standard work and kaizen.

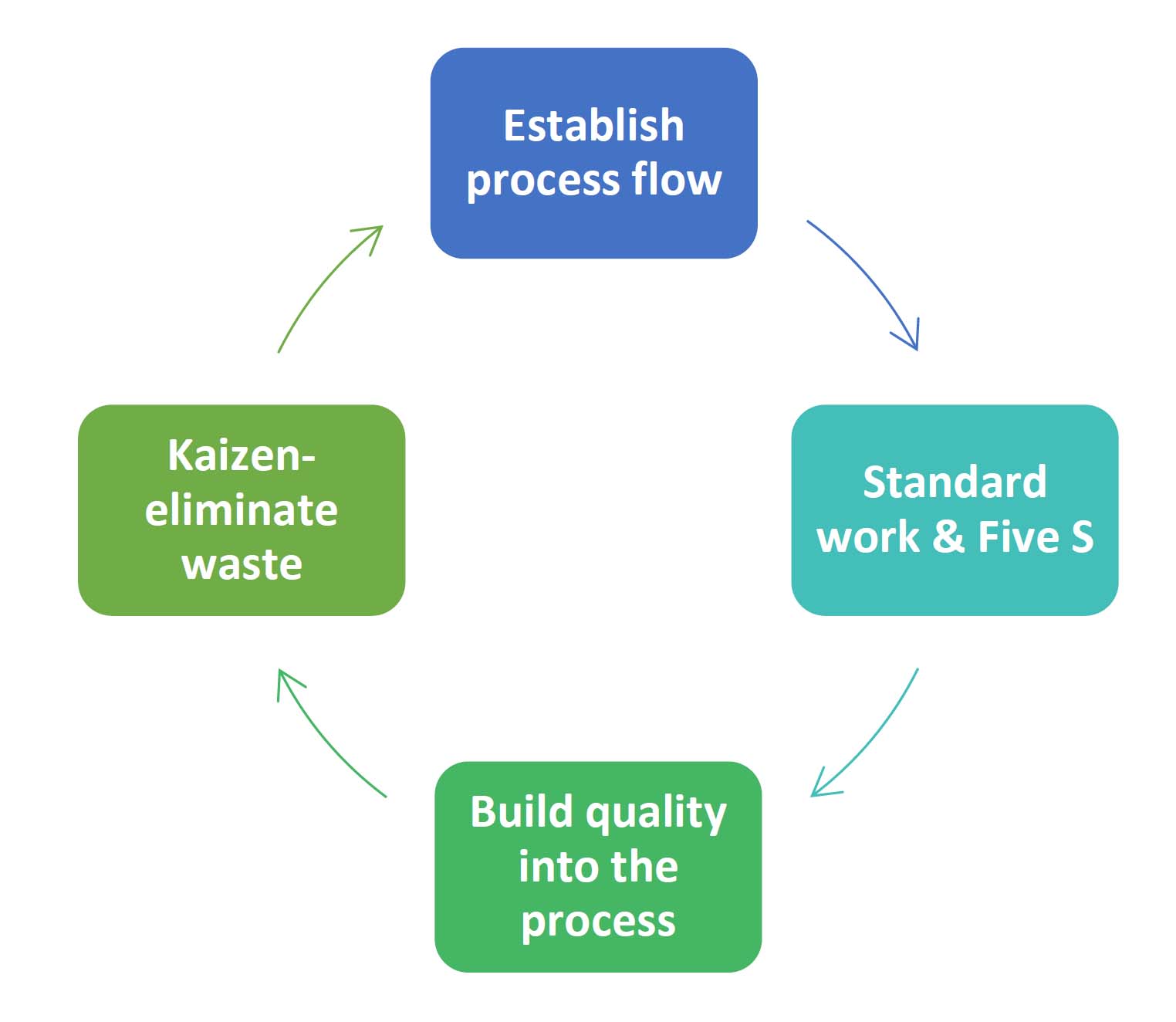

You first bring order and stability by organizing the process and establishing standard work. You then ensure quality is built into the process. Last, you improve the process by eliminating waste and continuing to improve quality. The cycle looks as follows:

As you follow this cycle, it will help you reach the goals of 1) highest quality, 2) shortest lead time, and 3) lowest cost. Once you use individual kaizen to eliminate waste from the process, the new process becomes the new standard work and the cycle repeats itself. What wastes will you eliminate from your process today?